About the Artist

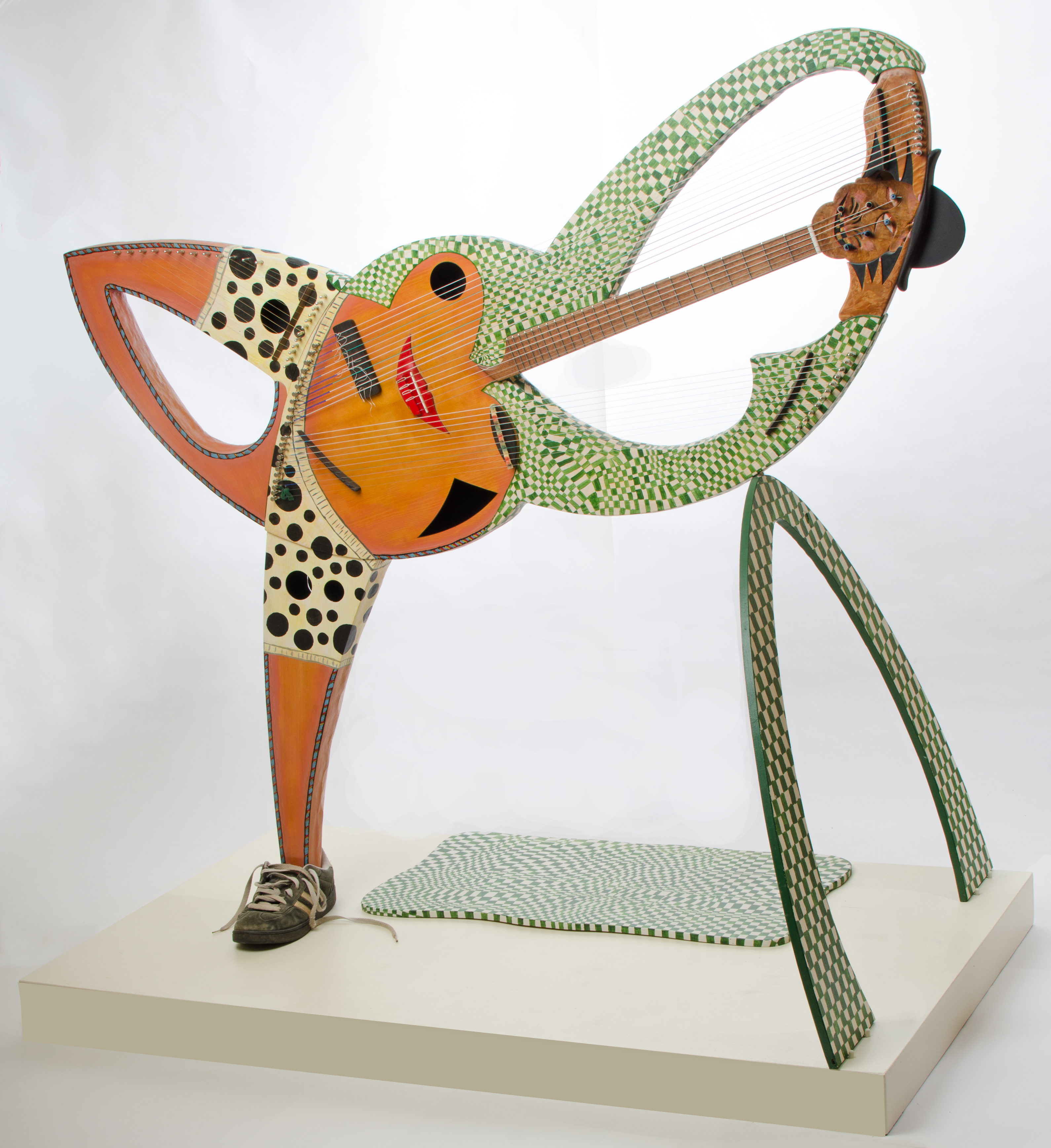

Innovative California luthier Fred Carlson got his start in rural Vermont, where as a teenager in the early 1970s he worked with artist Ken Riportella, a maker of musical sculptures. In 1975 Fred studied guitar-building with acclaimed lutherie teacher Charles Fox. Throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s Fred built and repaired stringed instruments professionally in a collective craft and woodworking studio that was run by members of the communal farm where he lived for some 20 years. In 1984, Fred’s violin-building partner, Suzy Norris, inspired him with her use of sympathetic strings to develop the Sympitar, a guitar with internal resonating strings. In 1985 Fred showed a prototype of the Sympitar to guitarist/composer Alex de Grassi, who still performs and records with one of the early Sympitars that his feedback helped evolve. Moving to California in 1989, Fred has continued to expand the aesthetic and functional boundaries of the guitar with instruments like the Harp-Sympitar, the Barikoto and the Banjalarpe, original designs that are acoustically and aesthetically adventurous while maintaining the important functional qualities of fine musical instruments, and honoring the traditions of the craft.

Artist Statement

As a teenager some 45 years ago, I got involved in making musical instruments because I wanted to make myself a banjo. I was living in commune in rural Vermont, filled with woodworkers and musicians. A woman there played old-time 5-string banjo, and I desperately wanted to learn how to do that. We built all our own houses there, and there were some very skilled cabinet makers that I got to rub shoulders with. It occurred to me that I could probably build a banjo if I had some help. I was attending a very small, alternative high school program at the time, and I asked the director if he could find someone to help me build a banjo. That led me to working for several years with a wonderful artist/sculptor, Ken Riportella, who was making Appalachian dulcimers in wild, sculpted shapes. I did eventually make myself a little wooden banjo that I traveled everywhere with, learning to play old mountain tunes and songs. I sewed a case for it out of an old raincoat I got from the Catholic Daughters Rummage Sale, an annual event in Montpelier, Vermont, that was run by octagenarian identical twin ladies who wore matching plaid outfits. That was about as good as a rummage sale gets, and those were happy, innocent days in my life.

I got distracted, then, by guitar making, and by becoming a “professional” luthier, something I studied and practised seriously for many years. But, my natural tendancy has always been toward creativity; I gravitated towards unusual shapes and gradually my work got more assymetrical, farther away from traditional guitar making. I always wanted to use color, and to have the wood be more plastic than it is, to be able to get shapes that don’t come easy with a chisel.

In a parallel thread of my life, I was doing a lot of theater performance, and got interested in mask-making, strongly influenced by the work of Peter Schumann, of Vermont’s Bread and Puppet Theater. At some point, I began to get the urge to combine the mask-making with the instrument building; it seemed that a large mask might make a really great resonating shell (back) for a stringed instrument.

Over the years, as I got more involved in making more and more complicated variations on multi-string harp guitar things for clients, I made an occasional foray into the mask-as-a-back idea. It was fun, and I began to develop a paper-and-glue laminate material that had the right consistency to make a reasonable resonator.

It has been only in the last couple of years that I’ve gotten back into banjo building, and have discovered that this papier-mache material is well suited for making a banjo shell/back. The original ancestors of our modern banjo came from Africa, and were basically gourds with skin stretched over them. I tried growing gourds…the climate where I now live in coastal California isn’t right. But I realized I could make my own gourd substitute using my papier-mache material, and have control over shape, color and so on.

So, I’ve been reinventing the ancient, African gourd banjo using recycled Safeway paper grocery bags and Titebond glue. One thing that draws me to the banjo is an amazing fact of its existence: it came to us through so much suffering, a people forced into slavery and servitude for centuries, and somehow the instrument is universally associated with joy. My most recent work has been in trying to manifest that joy into the sculpture of the instrument.